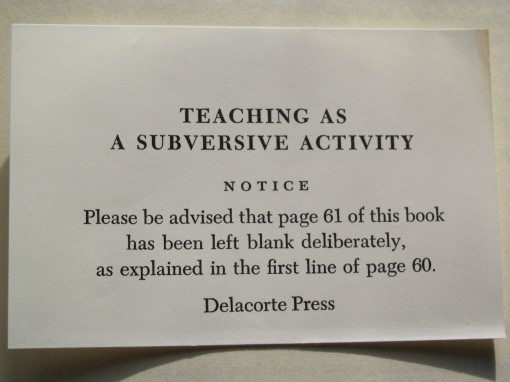

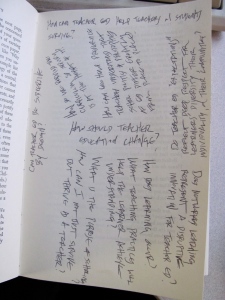

I recently discovered Teaching as a Subversive Activity by Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner—or, rather, it found me—thanks to Bud Hunt’s recommendation. The book’s famous hallmark is the intentional blankness of page 61. In a chapter on “What’s Worth Knowing?”, the authors invite readers to engage in inquiry-driven marking-up by writing their own questions on page 61.about what’s worth knowing. For most people who grew up thinking of books—BOOKS!—as repositories of authoritative, received, vetted, static knowledge, as things to be handled with respect, the idea of writing in one, even when invited, feels like vandalism. Even though Postman would say the reader’s act of writing on page 61, of modifying the text and becoming a flash-collaborator, is an act of higher respect.

Page 61 is a subversive—even magical—space, a prescient glimpse ahead of its time at the read-write revolution that would come 40 or so years later.

First, it challenges our traditional, comfortable notions of book and reader by changing both into something new. By inviting alteration (you could even say requesting or demanding it), the book stops being a book in the way we usually think of it, or at least the way a 1969 reader thought of it. It stops being a static repository of received knowledge and becomes something more fluid, harder to pin down. Even the structure changes—where we expect a bunch of text, we suddenly have this space we’re not quite sure what to do with.

And second, by writing in the book, the reader changes from passive consumer to active participant and content producer. Whatever’s written on page 61 alters the meaning of the book and the next reader’s learning. Page 61 is a built-in invitation to engage in inquiry, to act, to learn and change. But in most copies, that blank page is still blank 40 years later. The subversive potential goes unexplored, and we remain stuck in our old familiar patterns.

I checked out my university library’s copy. Yep. Blank. Gotta do something to remedy that.

At roughly the same time, Alec Couros and Dean Shareski posted a “call for insights” for their Educon 2.2 presentation about the changing role of teacher education.

The topic: “(Re)Imagining Social Media and Technology in Teacher Education.”

The questions:

- What are your general views on the status of teacher education in preparing teachers, especially in regards to innovative teaching? What positives, negatives, or general views can you share? Please do pull in your own experiences if applicable.

- What is the ideal role of teacher education in developing teachers who are media literate and technologically savvy?

Their prompt got me thinking that Postman’s subversive Page 61 might serve as a compelling metaphor for the kinds of conversations and disruptions happening in, around, and about teacher education. Here’s my rambling attempt at a response. Don’t be distracted by the stunning production values and Clooney-esque delivery.