For a variety of reasons, some closer to home than others, I’ve been trying to pay attention to the dynamics and politics of power, especially in the arena of teaching and learning. How we opt into systems and practices that compel, constrain, control, and commodify learners. How we are so often willing to wield subtle brands of force in the name of compliance and accountability, how lightly and conveniently we dismiss what should make us deeply uncomfortable, how central the blind spot that allows us to miss seeing vulnerability victimized by power.

In organizations where a command-and-control philosophy is running the show, everyone’s sense of identity is threatened. Everyone ends up living, as Parker Palmer puts it, a divided life. Command-and-control may be in charge above ground, but the underground is really where it’s at. It’s the resistance movement. It’s where creativity and humor and honesty and trust go to ground. It’s where people go to keep alive the other half of their divided life, and where they make plans for stitching it all back together.

One of my friends—an experience, dedicated, caring, smart teacher—teaches in a setting where power politics run rampant and trust is absent. Our conversations often circle back to the question of how to cope, survive, hopefully thrive in a toxic place. Going underground is one way. Finding a more generative source and definition of power is another.

She gave generous permission to share these reflections. They’re not necessarily easy to hear, but I think they’re important. And, yes…powerful.

It’s been interesting (and sometimes painful) to see how my principal has managed (or mismanaged) the power he has to influence and effect and affect change. At first, I got the feeling there was a naivete about what he was doing. I thought of Zeus as a teenager – who suddenly discovers he has lightning bolts and flings them around arbitrarily, unaware that the “little people” on earth are being hit by those bolts. Now – I see that he is fully aware of his power and uses it to bully, intimidate, alienate, and squash anyone who has any type of opinion or thought that varies from his own. It’s immensely sad and frightening to watch – and very painful when you are the one being targeted.

And along with this, I’ve learned a lot about my own response to and need for power. I’ve had to examine what “power” and control mean to me – and realize that I have an immense amount of both – and very little of both – all at the same time. Right now, I am stuck in a hostile environment of distrust, where the rules are constantly changing, and I am always in “trouble” even when I’m trying to follow what I thought I was supposed to do. I work in a state of “eggshell fear” – never knowing when I am going to say or do the wrong thing and be humiliated or reprimanded for things I used to be praised for. It would appear that I am completely powerless, completely at the whim of a teenage dictator, an absolute victim. And that has made me turn within and really examine how much personal power I have and how much power I still retain (in little bits) to positively impact the lives of my students. That is where I still feel that I do have power and I do have control.

Although I’ve always had a keen understanding of (and respect for) the power I carry as a teacher, I have become even more aware of that – and careful of how I utilize power in my classroom with my students. I have spent the last three years being a student myself, thrown into a situation where it is important for someone else that I feel powerless and victimized and “know my place” and I have become even more aware of how my students feel as children in an adult world of power.

It’s been an incredibly difficult few years but I feel like I’ve arisen as a stronger, better, different person. I’m finally starting to feel like I’ve found my center again – something I wasn’t sure, until just a few months ago, that I would ever reclaim again.

Strength is its own kind of power.

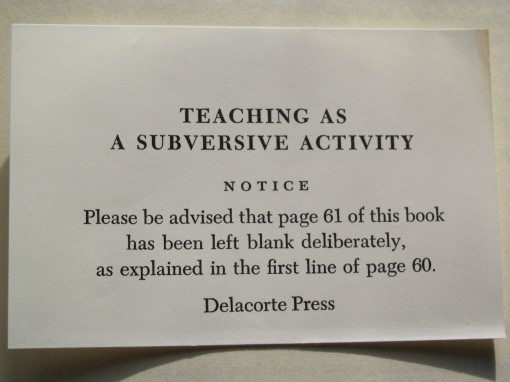

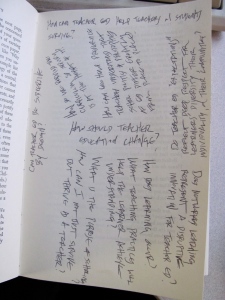

But beyond—or beneath—what it’s designed to do is what it’s NOT designed to do. Remember, we’re talking about unpredictable humans here. Plug them into a structure like a conference and they’ll immediately start misbehaving and getting up to all sorts of no-good goodness. Their attention will wander. They will not follow directions. They’ll make up their own. They will be snarky. They will criticize. And they should. They will tinker in the margins, in the aisles, at the back of the room, wherever they can find a place to plug in. They will invent ways to make it fit their learning. They will hack the structure.

But beyond—or beneath—what it’s designed to do is what it’s NOT designed to do. Remember, we’re talking about unpredictable humans here. Plug them into a structure like a conference and they’ll immediately start misbehaving and getting up to all sorts of no-good goodness. Their attention will wander. They will not follow directions. They’ll make up their own. They will be snarky. They will criticize. And they should. They will tinker in the margins, in the aisles, at the back of the room, wherever they can find a place to plug in. They will invent ways to make it fit their learning. They will hack the structure.